Robert F. Maslowski, Archeologist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (retired).

A paper presented the Fifth World Archeology Conference, Washington, DC, June 2003

© 2003 Robert F. Maslowski

Abstract

The Great Kanawha Navigation system originally included ten Chanoine dams on the Kanawha River in southern West Virginia. The French system was completed in 1898 and provided for year-round water transportation for 90 miles of the Kanawha River from Boomer to Point Pleasant, on the Ohio River. The ten locks and dams were replaced with four high lift dams with German roller gates in the early 1930s. Gallipolis was built on the Ohio River and Winfield, Marmet and London were built on the Kanawha. Beginning in 1989 three of these Locks and Dams were improved by adding additional lock chambers. Land required for these improvements totaled 1854 acres and included 69 archeological sites. Twenty of these sites (29%) were determined eligible for the National Register. Fourteen sites required data recovery. Six sites including the Clover National Historic Landmark were preserved and three sites were partially preserved. The cultural components at these sites included much of the prehistory and history of the Kanawha Valley and southern West Virginia from Late Paleo Indian to A. D. 1900. Data recovery resulted in major contributions to prehistoric, historic and industrial archeology and bioanthropology. This paper discusses the data recovery results, preservation efforts and public archeology.

Introduction

The United States Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) is made up of approximately 34,600 civilian and 650 military men and women. The organization is comprised of a diverse workforce of archeologists, biologists, engineers, geologists, hydrologists, natural resource managers and other professionals. The Army Corps of Engineer’s mission is to provide quality, responsive engineering services to the nation. This mission includes planning, designing, building and operating water resources and other civil works projects such as navigation, flood control, and environmental protection.

The Corps is divided into Divisions and Districts based on watershed systems. The Huntington District is a part of the Lakes and Rivers Division and includes the area of five states drained by the Ohio River from New Martinsville, West Virginia, to just above Cincinnati, Ohio. The area drained by the Kanawha River includes the heart of Appalachia, southern and central West Virginia, and the New River drainage in Virginia and North Carolina.

The Corps constructed the Great Kanawha Navigation system in West Virginia as a cost effective means to move coal, salt, lumber, cement and chemicals along the Kanawha River (Kemp 2000). The original system consisting of ten French Chanoine shutter-wicket dams was completed in 1898. This system was replaced in the 1930s with four dams using the German roller-gate system. These locks and dams included Gallipolis (Robert C. Byrd) on the Ohio River, and Winfield, Marmet and London on the Kanawha River.

In 1974 Congress passed the Moss-Bennett Bill requiring federal agencies to be responsible for their own compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. Previously, responsibility for cultural resources surveys of Corps construction projects was delegated to the National Park Service. The Army Corps of Engineers responded by hiring archeologists, historians and anthropologists in their Planning Divisions and integrating cultural resources management into their planning process. As a result the Corps is responsible for the protection of thousands of archeological sites and archeological collections.

Corps projects are generally designed for a 50 year life span, so projects are continuously being upgraded and rehabilitated. Planning for the upgrade of the Kanawha Navigation System began in the late 1970s.

RC Byrd Locks and Dam (formerly Gallipolis) is located on the Ohio River approximately 9 miles downstream from Gallipolis, Ohio. The navigation pool stretches 41.7 miles along the Ohio River from the Racine Locks and 31.1 miles up the Kanawha River. The Corps conducted a cultural resources reconnaissance of the 600 acre locks and dam replacement study area in 1978 and recorded 26 archeological sites (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers 1978). Construction of the lock replacement project began in late 1987 and archeological data recovery on five sites was undertaken in 1988 and 1989 (Clay and Niquette, eds 1989, Niquette, Clay and Walters 1988, Shott 1990).

The Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area (GBWMA) was purchased as Fish & Wildlife Mitigation land for the Gallipolis Project. It is located in Cabell County, sixteen miles north of Huntington, West Virginia. The project area includes 836 acres, of which 126 acres are considered high-quality wetlands. An archeological survey of the GBWMA recorded 18 sites, 6 of which were determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places (Hughes and Kerr 1990, Hughes and Niquette 1989).

Winfield Locks and Dam is located in Putnam County, West Virginia, on the Kanawha River approximately 25 miles downstream from Charleston, West Virginia, and approximately 31 miles upstream from the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers at Point Pleasant, West Virginia. The project area contains a total of 300.0 acres and 11 archeological sites (Hand et al. 1988, Kerr et al. 1989). Archeological data recovery was undertaken at three National Register Eligible sites, Parkline (46PU99) (Niquette and Hughes 1991), the Corey Site (46PU100) (Hughes and Niquette, eds. 1991) and the Winfield Lock Site (46PU4) (Hughes and Niquette 1992).

Marmet Locks and Dam is located in Kanawha County, West Virginia, on the Kanawha River, a short distance above Charleston. The navigation pool stretches approximately 15 miles to London Locks and Dam. The project area contains a total of 118 acres, and 14 archeological sites including six National Register Eligible sites (Anslinger et. al 1996, Updike et. al. 2000). Highlights of these data recovery and preservation projects are presented in chronological order.

Prehistoric Archeology

Base of the Clovis point from Kirk

MoundFluted point

Carved sandstone bowl, c. 3000 BP

Only two sites in the project areas produced Paleo Indian artifacts (10,500 BC). The base of a Clovis point associated with mound fill was recovered from the Kirk Mound, a plowed down mound excavated as part of the RC Byrd Project (Niquette et al. 1988). Two Late Paleo points (9000 BC) were recovered from the basal layers of the Van Bibber Reynolds site at Marmet.

The most significant Early Archaic component was a bifurcated base component (6000 BC) excavated at the Van Bibber Reynolds Site at Marmet.

While Late Archaic components (3000 – 1000 BC) were found throughout the project areas, the most significant find was the buried Late Archaic component at the Burning Spring Branch Site (46KA142). This site contained significant information on the transition from imported steatite bowls to locally made sandstone bowls and finally Early Woodland pottery and is an example of Late Archaic technology transfer. Steatite is not found in the local area; the closest sources are in Virginia. A few steatite bowls have been found at the Burning Spring Branch site and other sites along the Kanawha River. These were rapidly replaced by bowls made of local sandstone. The general shapes and sizes of the bowls are identical to the shapes and sizes of steatite bowls from Virginia.

The Woodland (1000 BC – AD 1200) settlement patterns in the project area consist of scattered hamlets located along floodplain and terraces on the Kanawha and Ohio Rivers. Several Early Woodland pits were excavated at the Winfield Lock Site and the Burning Spring Branch site. These provided radiocarbon dates and good physical descriptions of the earliest pottery recovered in southern West Virginia.

Adena ceremonial circle at the Neibert Mound site

On the basis of excavations conducted at the Gallipolis project, the Middle Woodland Period was redefined to include Adena, the cultural-historical complex associated with conical burial mounds. The Kirk and Newman Mounds and an Adena ceremonial circle at the Niebert Site were totally excavated. This provided for new interpretations of Adena ritual associated with burial mounds (Clay 1998, Clay and Niquette 1992). The paired post circle at Niebert consisted of outward sloping posts forming an open air structure. No artifacts were found in the structure but one large pit contained charcoal and fragments of cremated human bone. The structure was interpreted as a place where bodies were cremated and the remains reburied in local burial mounds like Kirk and Newman.

The most significant early Late Woodland Site excavated was the Childers Site (46MS121) which consisted of a settlement dating to A.D. 650, surrounded on three sides with a ditch (Shott 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993). The site was interpreted as an intrusive village site (Shot and Jefferies 1992, Shott et. al. 1993) but a recent reevaluation of the data suggests it may have been a seasonally occupied settlement.

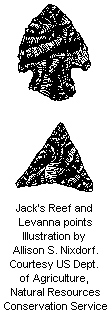

Late Woodland points

Parkline (46PU99), a Late Woodland hamlet (A.D. 700 to 900) at Winfield, represents one of the first Intrusive Mound habitation sites excavated in the Ohio Valley (Niquette and Hughes 1991, Niquette and Kerr 1993). It produced characteristic decorated pottery in association with Jack’s Reef and Levanna projectile points which is thought by many to represent the initial introduction of the bow and arrow into the area.

The Woods Site (46MS14) at Gallipolis represents a series of hamlets dating from A.D. 900 to 1100 (Shott 1989, 1990, Shott and Jefferies 1992). These hamlets provide information on the transition from Eastern Agricultural Complex horticulture to corn agriculture and appear to be the Woodland base that develops into local Fort Ancient Village sites at A.D. 1200 (Wymer 1986, 1990, 1992).

A Late Prehistoric (AD 1200-1550) Fort Ancient Village (46CB98) dating to AD 1300 (Maslowski et al. 1995:50) has been tested and preserved at the Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area (Hughes and Kerr 1990:144).

A unique Late Prehistoric Fort Ancient Village dating to AD 1500 was entirely excavated as part of the Burning Spring Branch Site (46KA142) at Marmet. It was a stockaded village with 25 rectangular structures and 25 burials. It is unique because the lack of a characteristic Fort Ancient midden, the relatively small number of burials and poor bone preservation due to a lack of associated mussel shell. These characteristics indicate the village was occupied a few years and abandoned. This may be the only Fort Ancient Village in the Ohio Valley that has been entirely excavated using modern excavation techniques. Analysis on the village is under way and will continue for three or four years. It is expected that this component will provide significant information on the internal structure and social organization of the village, the possible construction sequence for the village and the basis for the development of a local Fort Ancient pottery chronology.

Late Prehistoric and historic components at Marmet

The most significant site encountered in the Kanawha Navigation Project is the Clover Site (46CB40), the type site for the Clover Complex (Griffin 1943, Maslowski 1984, Mayer-Oakes 1955). This Protohistoric Village dating to AD 1600 was designated as a National Historic Landmark and is federally protected as part of the Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area. Besides the characteristic lithics and pottery, Clover has well preserved burials, bone artifacts in all stages of production, and shell artifacts. It is one of the Protohistoric villages that may eventually be connected with historic Indian tribes.

Historic and Industrial Archeology

The Marmet project had some of the most significant historic sites excavated in West Virginia. The Burning Spring Branch area, originally owned by George Washington, was in the center of the Kanawha Valley Salt Industry. Four early salt furnaces (Updike 2001), a slave cabin, the John Reynolds Mansion and associated out buildings, and two historic cemeteries were excavated as part of the Marmet Project (Updike 1999). The first salt furnace in the Kanawha Valley (often referred to today as Chemical Valley) was built in 1797. During the early 1800s the Kanawha Valley had over 50 salt furnaces and was the center of salt production in the United States. It developed the first cartel to control salt production and prices and developed the technology that was later used in the oil, gas, coal and chemical industries (Updike 2003a).

The John Reynolds Mansion was located near the mouth of Burning Spring Branch on the Burning Spring Branch Site (46KA142) approximately one hundred yards from an early salt furnace. The house was described in an early newspaper article as a “white frame mansion.” Features documented at the site included a sandstone foundation with interior root cellar, an exterior root cellar, a stone-lined privy, a second later privy, a barn, a well or cistern and a chimney base suggesting the presence of a second house (Updike 2003b).

Pierced coin, a common slave talisman,

with an historic period pipe in the background

The Willow Bluff Site (46KA352) had the remains of a double fire hearth that suggested the presence of a log cabin occupied by industrial slaves rented from Virginia plantations. The presence of lower cost ceramics such as edge-decorated plates, redware, and copies of refined earthenware bowls, lower status cut of meat such as the heads and lower limbs of hogs, and pierced silver coins and pierced metal objects indicate the presence of slaves (Updike 2002).

At the Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area extensive test excavations were undertaken at the General Albert Gallatin Jenkins House, a National Register structure that is located on a National Register Eligible archeological site. Jenkins was a Confederate General during the Civil War. The House was built by his father, William Jenkins, in 1836 and was at the center of a 4000 acre plantation that included over 50 slaves at the height of its operation. Beneath the Jenkins occupation are stratified prehistoric Fort Ancient and Woodland occupations.

Test excavations were undertaken to find the outbuildings associated with the house and to determine the extent of archeological investigations that will be required for mitigation if the house and outbuildings are restored as a historic site and tourist attraction. So far an office, kitchen, root cellar, privy and two brick sidewalks have been uncovered along with thousands of historic artifacts that will be used to interpret the site.

Bioanthropology

Two historic cemeteries were excavated as part of the Marmet project. The Burning Spring Branch Cemetery was a small, rural cemetery likely containing interments associated with John Morris, a Euro-American pioneer who purchased the tract in 1795 and reserved cemetery rights upon its sale in 1818. The spatial organization was characteristic of an upland south folk cemetery, and burials were aligned in rows or clusters suggestive of a single, possibly extended, family. The lack of ostentation in the cemetery epitomizes the early American view of death (Bybee 2002). Although preservation was generally poor, human remains were recovered from eight of the nine interments. An articulated skull and other intact and fragmentary skeletal remains provided general biological data, while human hair samples provided information on racial affinity. Dental elements offered a variety of information regarding health and age-at-death for the interred population.

The Reynolds cemetery (46KA349) dated from 1832 to 1900. It had 31 burials which included John Reynolds and possibly nine other Reynolds family members (Bybee 2001). The transition from hexagonal coffins to rectangular caskets after the Civil War is documented. This reflects the changing attitudes toward death. Greater emphasis and romanticism was placed on death as a natural design, linking the deceased with the universe. This “beautification of death,” as it came to be known, also meant a prolonged period of mourning and more elaborate coffins and gravestones.

Preservation

While the Kanawha Navigation Project provided the opportunity for extensive archeological excavations which contributed to the interpretation of local and regional prehistory and history, it also provided for the preservation of several archeological sites and the rehabilitation of the one National Register structure, the Albert Gallatin Jenkins House. Table 1 shows the number of acres at each project, the number of archeological sites and the number of sites designated as National Register Eligible (NR).

| Project | Acres | Hectares | Sites | NR |

| Gallipolis (RC Byrd) | 600 | 243 | 26 | 5 |

| Green Bottom | 836 | 338 | 18 | 6 |

| Winfield | 300 | 121 | 11 | 3 |

| Marmet | 118 | 48 | 14 | 6 |

| London | (No Land) | |||

| Totals | 1854 | 750 | 69 | 20 |

With the purchase of the 836 acre Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area for wetland mitigation at the RC Byrd project, the Corps was able to record and evaluate 18 additional archeological sites. Six of these sites were determined eligible for the National Register and one of these, the Clover site, was subsequently placed on the National Register and designated a National Historic Landmark. All of these sites are preserved and because of their federal ownership they are protected under the National Historic Preservation Act, Title 36 and the Archeological Resources Protection Act.

At the Marmet project, all 14 archeological sites were scheduled to be destroyed by construction or disposal activities. By putting the archeological information into a Geographical Information System (GIS) and overlaying it on the construction plans, it was determined that portions of four sites could be preserved. A pipeline proposed to be relocated through sites 46KA223, 46KA399 and 46KA352 was relocated out of the project area. The GIS helped determine that a strip of land with buried Woodland and Late Archaic components between the lock excavation and the decant excavation on the Burning Spring Branch site could be preserved. Under the present plan 0.74 acres (0.30 hectares) of the Woodland component and 0.88 acres (0.36 hectares) of the Late Archaic component can be preserved. The Project Management Team is now looking at slight design modifications that could preserve larger portions of the site.

Public Archeology

At the beginning of the Kanawha Navigation Project, data recovery was rather straight forward. Sites were excavated, analyzed and technical reports were written and distributed to the academic community in small numbers. Today there is more emphasis on making archeological findings available to the greater public and there is more public participation in archeological projects. Beginning with the Marmet project archeological articles were specifically written for Wonderful West Virginia (Birdwell 2001) a popular magazine highlighting the State’s natural resources and tourist attractions. A film on the historic archeology at Marmet, Red Salt and Reynolds: A Kanawha Salt Makers Story, is being completed for public television and distribution to local schools and the general public. Another film on the prehistory of the Kanawha valley is in the initial production stages.

At Marmet the relocation of the Reynolds Cemetery was coordinated with related families who were located through the internet. Information about the excavations was distributed through the Van Bibber Family Genealogical Newsletter and as additional genealogical information was discovered it was made available to the related families. When the Fort Ancient Village was uncovered at the Burning Spring Branch site there was a high probability of finding Native American burials, and coordination with 17 Federally Recognized Indian tribes was initiated. The excavations were also coordinated with local Native American groups who toured the excavations.

The Green Bottom Wildlife Management Area proved to be a more complex situation in terms of public involvement. The local Greenbottom Society and the West Virginia Division of Culture and History are interested in restoring the Albert Gallatin Jenkins House, the home of a Confederate Civil War General (Birdwell 2003). This National Register house is presently maintained and operated by the West Virginia Division of Culture and History as the Jenkins Plantation Museum. It is located on a National Register Eligible archeological site and besides the historic Jenkins occupation, there are stratified Fort Ancient and Woodland components to the site. The United States Congress has authorized the Corps to restore the house even though it is located in a 20 year flood frequency. The interested parties maintain that restoration of the house includes all of the associated out buildings so extensive test excavations were undertaken to locate evidence of the outbuildings. The Corps has set up a committee that includes representatives from the Greenbottom Society, West Virginia Division of Culture and History and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). An office, kitchen, privy, cellar and two brick sidewalks have been archeologically identified and a restoration plan is in the initial development stages.

Discussion

The Appalachian Mountains are a loose group of peaks and ridges stretching 1,100 miles parallel to the Atlantic coast. The Kanawha drainage is located in central Appalachia in the Appalachian Plateau which has peaks up to 4000 feet and a highly dissected dentritic drainage pattern.

In the course of prehistory Appalachia was occupied by a fairly uniform Paleo-Indian culture by 10,500 BC. Regionalization gradually occurred during the Archaic period and by 1000 BC central Appalachia was a multi-cultural area and continues to be so into the present.

Unlike the Mississippian chiefdoms to the south and west and the Powhattan chiefdom to the east, Native American cultures in Appalachia never evolved beyond a tribal level of society.

In terms of European settlement Appalachia, is traditionally characterized as a Scots-Irish population but in reality there were many waves of immigration with many different cultures represented. The archeological excavations undertaken as part of the Kanawha Navigation Project have brought many of these groups together and all have various interests in the preservation, use and interpretation of the Huntington District’s archeological sites.

Native Americans are represented by federally recognized tribes that include Cherokee, Iroquois, Shawnee and Delaware. Several other local non federally recognized Native American groups are also represented.

European groups consist of the local historical and archeological societies, descendants and relatives of the Reynolds and Jenkins families and in the case of the Jenkins Plantation, Civil War reinactors. All are interested in various aspects of the interpretation of the archeological and historical data.

African-Americans are represented by the local chapter of the NAACP. The history of African-Americans is generally connected to the interpretation of plantation slavery in the south. The excavations of the Willow Bluff slave cabin has provided the basis for the interpretation of industrial slavery in Appalachia. The excavations at the Jenkins Plantation provide for the interpretation of a plantation system that was moved from east of the mountains to what, at that time, was the edge of the wilderness.

The Jenkins Plantation is unique because it brings all of these perspectives into one project and forces the Corps to address the issues of the local history of Native Americans, African-Americans and Europeans in a regional and national context because Congress has authorized the restoration of the Jenkins house. The historic house and the associated archeology will provide an opportunity for the local and regional interpretation of the American Civil War in a national context.

Conclusions

William Duncan Strong (1947:210) wrote "From time immemorial the river valleys of the world have been the trade routes and living centers of human society. It might be estimated, as it has for the region of the United States, that some 80 % of all the archeological remains in the world occur in only two per cent of its area, that is bordering or in conjunction with river valleys." The archeology of the Great Kanawha Navigation System with 20 National Register Eligible sites located on 1854 acres of land clearly supports this statement. Because of its navigation and flood control responsibilities the Corps, nationwide, is significantly involved in the preservation and interpretation of the archeology and history of the nation.

References

Anslinger, C. Michael, Henry S. McKelway and Jeffrey G. Mauck

- 1996 Phase I and II Archeological Investigation for the Marmet Lock Replacement Project, Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 96-08.

Birdwell, Leslie

- 2001 Salt, Settlers, and Slavery: Malden site a Microcosm of the Kanawha Valley’s Past. Wonderful West Virginia 65(11):2-11.2003 Unearthing Clues for Restoring Historical Homestead. Wonderful West Virginia 67(1):2-7.

Bybee, Alexandra D.

- 2001 Bioanthropological Investigations of the Reynolds Family Cemetery (46Ka349) in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV02-63.2002 Bioanthropological Investigations of the Burning Spring Branch Cemetery (46Ka142) in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV02-111.

Clay, R. Berle

- 1998 The Essential Features of Adena Ritual and Their Implications. Southeastern Archaeology 17(1): 1-20.

Clay, R. Berle and Charles M. Niquette (eds)

- 1989 Phase III Excavations at the Niebert Site (46MS103) in the Gallipolis Locks and Dam Replacement Project, Mason County, West Virginia. Report prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc. Contract Publication Series 89-06.

Clay, R. Berle and Charles M. Niquette

- 1992 Middle Woodland Mortuary Ritual in the Gallipolis Locks and Dam Vicinity, Mason County, West Virginia. West Virginia Archeologist 44(1&2):1-25.

Griffin, James B.

- 1943 The Fort Ancient Aspect. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Hand, Robert B., Jonathan P. Kerr, Myra A. Hughes and Charles M. Niquette

- 1988 A Phase One Survey and National Register Evaluations of 46PU4 and 46PU5A, Winfield Locks and Dam Replacement Project, Putnam County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 88-30.

Hughes, Myra A. and Jonathan P. Kerr

- 1990 A National Register Evaluation of Selected Archeological Sites in the Gallipolis Mitigation Site at Greenbottom, Cabell County, West Virginia. Report prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 90-08.

Hughes, Myra A. and Charles M. Niquette (eds)

- 1989 A National Register Evaluation of the Jenkins House Site and a Phase One Inventory of Archeological Sites in the Gallipolis Mitigation Site at Greenbottom, Cabell County, West Virginia. Report prepared for U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Huntington District. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 89-12.1991 Late Archaic Archaeology in the Lower Kanawha Valley: Excavations at the Corey Site (46PU100), Putnam County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 91-71.1992 The Winfield Locks Site: A Phase III Excavation in the Lower Kanawha Valley, Putnam County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 92-81, November 3, 1992.

Kemp, Emory L.

- 2000 The Great Kanawha Navigation. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh.

Kerr, Jonathan P., Myra A. Hughes, Robert B. Hand and Charles M. Niquette

- 1989 A National Register Evaluation of 46PU99, 46PU100 and 46PU101, Winfield Locks and Dam Replacement Project, Putnam County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 89-03.

Maslowski, Robert F.

- 1984 Protohistoric Villages in Southern West Virginia. Upland Archeology in the East, Symposium 2, pp. 148-165. James Madison University, Harrisonburg, Virginia.

Maslowski, Robert F., Charles M. Niquette and Derek M. Wingfield

- 1995 The Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia Radiocarbon Database. West Virginia Archeologist 47(1&2).

Mayer-Oakes, William J.

- 1955 Prehistory of the Upper Ohio Valley. Annals of Carnegie Museum, vol. 34, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Niquette, Charles M. and Myra A. Hughes (eds)

- 1991 Late Woodland Archeology at the Parkline Site (46PU99), Putnam County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 90-93.

Niquette, Charles M. and Jonathan P. Kerr

- 1993 Late Woodland Archeology at the Parkline Site, Putnam County, West Virginia. West Virginia Archeologist 45(1&2):43-59.

Niquette, Charles M., R. Berle Clay and Mathew M. Walters

- 1988 Phase III Excavations of the Kirk (46MS112) and Newman Mounds (46MS110), Gallipolis Locks and Dam Replacement Project, Mason County, West Virginia. Cultural Resource Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series 88-11.

Niquette, Charles M., Elizabeth H. Tuttle, and Gerald Oetelaar

- 1988 Phase III Excavations at the Niebert Site (46MS103): The Historic Component, an Early 19th Century Rural Home Site in Mason County, West Virginia. West Virginia Archeologist 40(1):1-31.

Shott, Michael J.

- 1989 Childers, Woods and Late Woodland Chronology in the Upper Ohio Valley, West Virginia Archeologist 41(2):27-40.1990 Childers and Woods: Two Late Woodland Sites in the Upper Ohio Valley, Mason County, West Virginia. University of Kentucky Program for Cultural Resource Assessment, Archeological Report 200.1992 Radiocarbon Dating as a Probabilistic Technique: The Childers Site and Late Woodland Occupation in the Ohio Valley. American Antiquity 57(2): 202-230.1993 Spears, Darts, and Arrows: Late Woodland Hunting Techniques in the Upper Ohio Valley. American Antiquity 58(3): 425-443.

Shott, Michael J. and Richard W. Jefferies

- 1992 Late Woodland Economy and Settlement in the Mid-Ohio Valley: Recent Results from the Childers/Woods Project. In Cultural Variability in Context: Woodland Settlements of the Mid-Ohio Valley, edited by Mark F. Seeman, Pages 52-64.

Shott, Michael J., Richard W. Jefferies, Gerald Oetelaar, Nancy O'Malley, Mary Lucas Powell and Dee Anne Wymer

- 1993 The Childers Site and Early Late Woodland Cultures of the Upper Ohio Valley. West Virginia Archeologist 45(1&2):1-30.

Strong, William Duncan

- 1947 The Coordinated River Valley Approach—A World Problem. In Symposium on River Valley Archeology, J.O. Brew et al., American Antiquity 12(4).

U. S. Army Corps of Engineers

- 1978 Gallipolis Locks and Dam Replacement Study, Ohio River, Cultural Resources Reconnaissance. Huntington District.

Updike, William D.

- 1999 Historic Period Research for the Marmet Lock and Dam Replacement Project, Lower Belle, Kanawha County, West Virginia. West Virginia Archeologist 51(1&2).2001 Archaeological Data Recovery for the Red Sand (46Ka354) and Terrace Green (46Ka356) Sites, Marmet Lock Replacement Project, Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV00-43.2002 Archaeological Data Recovery of a Historic African-American Slave Component at the Willow Bluff Site (46Ka352) in Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV02-19.2003a The Red Sand Site (46Ka354): Archaeological and Historical Investigations of a Nineteenth-Century Kanawha Valley Saltworks. In Great Kanawha Valley Chemical Heritage, Symposium Proceedings, Institute for the History of Technology and Industrial Archaeology, Monograph Series, Volume 6 (Lee R. Maddex, Compiler).2003b Speculation, Boom and Bust on the Great Kanawha: Phase II Testing and Archaeological Data Recovery for the Historic Component of the Burning Spring Branch Site (46Ka142), Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV03-16.

Updike, William D., C. Michael Anslinger and Andrew P. Bradbury

- 2000 National Register Evaluations for Four Sites Located within the Marmet Lock Replacement Project, Kanawha County, West Virginia. Cultural Resources Analysts, Inc., Contract Publication Series WV00-02.

Wymer, Dee Anne

- 1986 The Archaeobotanical Assemblage of the Childers Site: The Late Woodland in Perspective. West Virginia Archeologist 38(1):24-33.1990 Archaeobotany. Chapter 12 in Shott 1990, Childers and Woods: Two Late Woodland Sites in the Upper Ohio Valley, Mason County, West Virginia. University of Kentucky Program for Cultural Resource Assessment, Archeological Report 200, pp 487-616.1992 Trends and Disparities: The Woodland Paleoethnobotanical Record of the Mid-Ohio Valley. In Cultural Variability in Context: Woodland Settlements of the Mid-Ohio Valley, edited by Mark F. Seeman, pages 65-76.