by Dr. Robert F. Maslowski

© 2002 Robert F. Maslowski

The ancestors of American Indians came to North America from Siberia, which is today a part Russia. They came across the Bering Sea at a time when the ocean was much lower and there was a bridge of dry land between Alaska and Russia. Archeologists know very little about the earliest people who came across this land bridge but several different groups of people must have come across during several thousands of years. Archeologists know this because the American Indians have hundreds of different tribes that speak many different languages and have many different customs.

Twelve thousand five hundred years ago the last Ice Age was coming to an end and the Kanawha Valley was much different than it is today. The weather was colder and there were different types of plants and animals. The trees and plants were more like those found today in Alaska and northern Canada. Huge animals including the wooly mammoth and mastodon lived in the Valley. These animals died off shortly after the Ice Age came to an end. Animals like the caribou also lived here but moved further north as the weather became warmer and the trees and plants changed.

The earliest people in the Kanawha Valley are called Paleo-Indians. Paleo means old and the Paleo-Indians were the oldest inhabitants we know of in the Kanawha Valley. We know Paleo-Indians live here because archeologists have found their hunting tools called Clovis points in the mountains and along the river bottoms. Clovis or Fluted points are found all over the United States, Canada and Alaska. In the Western United States they are found with mammoth bones and radiocarbon dating indicates they are 12,500 years old.

Prehistoric people had the same basic needs as we have today. They needed food, shelter, clothing and tools. They had religious leaders, community leaders, and doctors to care for the sick. They had no schools but taught their children at home.

Paleo-Indians left very few remains in the Kanawha Valley. Archeologists believe they hunted Big Game animals like the mammoth and mastodon because their Clovis points have been found with mammoth remains in the western United States. They also hunted smaller animals and gathered numerous plants. We know that Paleo-Indians traveled a lot because they followed the game animals they hunted. Their Clovis points and other stone tools are often made of flint from Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia. Four of these points have been found along the Elk River in Charleston and Clovis points have also been found at Winfield, Poca Bottom near the John Amos Power Plant and Crown Hill.

About 10,000 years ago the Paleo-Indian period came to an end. The climate changed and became warmer. The plants and trees changed and became more like what is found in the Kanawha Valley today. Big Game including mammoth and mastodon became extinct and deer became abundant. Archeologists have named this the beginning of the Archaic Period. The Paleo-Indians changed their way of life to take full advantage of the new plants and animals and the warmer climate. They became the Archaic Indians.

The Archaic Indians did not travel as much as the Paleo-Indians. They no longer had to follow herds of Big Game animals. Instead they hunted deer which generally stay within one mile of their home unlike mammoth, mastodon and caribou. Hunting deer required new hunting techniques. The Archaic Indians did not make Clovis Fluted points for large hand held spears. They used much smaller spears and invented the spear thrower, or atlatl. They no longer made their stone tools from Ohio, Pennsylvania or Virginia flint but made them from Kanawha Black Flint, which was found right here in the Kanawha Valley.

The Archaic Indians were hunters and gatherers. Besides hunting deer, bear and other small animals such as wild turkey and rabbits, they caught fish and gathered many types of nuts, berries and wild plants. They lived in the Kanawha Valley from 10,000 to 3,000 years ago. About 4,000 years ago the Archaic Indians began using many types of wild seeds and began cooking their food in bowls carved of sandstone or soapstone.

As the number of Archaic Indians increased in the Kanawha Valley they began to experiment with growing some of their food. Sometime between 3,000 and 2,500 years ago the Archaic Indians became the Woodland Indians.

The Woodland Indians made many changes in the way they lived. They grew much more of their own food. They invented pottery for cooking and storing foods and they began building burial mounds. The Early Woodland Indians who lived in the Kanawha Valley were called the Adena People or the Mound Builders. They lived here from 2,500 to 2,000 years ago and during this time they constructed hundreds of earth and stone mounds in the Valley.

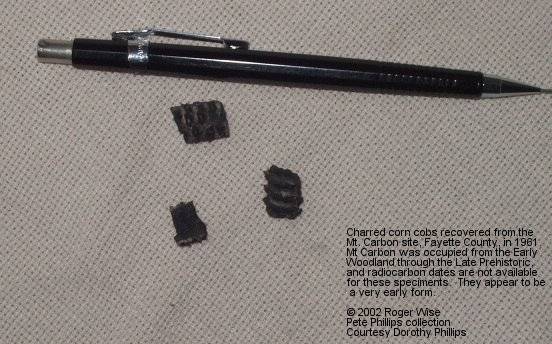

About 2,000 years ago the Middle and Late Woodland Indians quit building burial mounds. They continued making thinner and better pottery and domesticated several new plants including squash, gourds and several seed plants that we consider weeds today. About 1200 years ago the Woodland Indians began using the bow and arrow with its small triangular flint points. During this time Woodland Indians began planting corn which would become the major crop of the Fort Ancient Indians.

Through their history the Woodland Indians lived on small farms scattered throughout the Kanawha Valley. Even when they were building large burial mounds like the Criel Mound and the Great Smith Mound they had no large villages. This all changed 900 years ago with the development of the Late Prehistoric period and the Fort Ancient Culture.

About 900 years ago the groups of Woodland Indians banded together and built large circular villages on the high terraces along the Kanawha River. When these villages were built several changes took place among the local Indians. Corn, beans and squash became the major crops grown by the Indians. While the Fort Ancient Indians continued to use the abundant supply of nuts in the Kanawha Valley they no longer used the numerous wild and domestic seeds that were so important in the Woodland diet.

They gathered fresh water clams or mussels from the Kanawha River and many of these villages can be recognized today by the mussel shells scattered over the surface of the village.

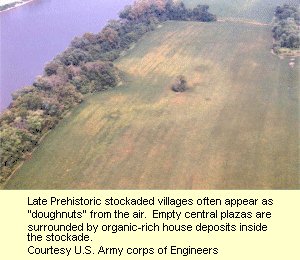

These villages were planned. Many were circular and had a stockade built of large posts. The villages had one or two rows of houses placed in a circle inside the stockade. The center of the village was an open plaza which was kept clean. When people died they were buried inside the village often beneath the house where the family still lived.

Some of these villages like Buffalo and Marmet were occupied well after Columbus discovered America. European trade goods such as glass beads, copper and brass ornaments were traded to the Indians and some of these have been found on Fort Ancient Village sites that date to 1600 AD.

The Fort Ancient Indians lived in the Kanawha Valley until 300 years ago when the Iroquois Indians from New York and the Great Lakes area drove them out. By the time the first settlers came to the Kanawha Valley all of the Indian Villages were gone and the area was used as a hunting ground by many historic tribes including the Iroquois, Shawnee and Cherokee.

Living in the Kanawha Valley

People have lived in the Kanawha Valley for the past 12,500 years. Archeologists have recorded only a small fraction of the sites that once existed in the valley.

Many different types of Indian sites have been recorded. These included small camp sites where Indians may have stayed from one day to several weeks as well as the large village sites of the Fort Ancient people which were occupied permanently just as our towns and cities are today.

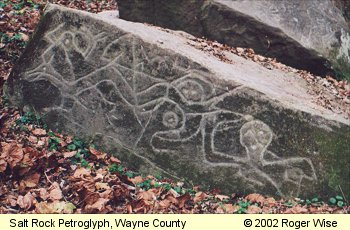

There are many special sites also like the mounds of earth or stone that were constructed by the Adena people to bury their dead and the petroglyphs (rock carvings) that had pictures of people, animals and animal tracks. Many rockshelters (rock overhangs) were occupied by groups of Indians traveling through the area along the Indian Trails or by families on hunting and gathering trips.

Who were the Mound Builders?

The early settlers in the Kanawha Valley believed a prehistoric race of people who they called "Mound Builders" once lived here. The settlers called these people Mound Builders because of the many burial mounds and earthworks they left behind. The early settlers believed the Mound Builders were an ancient vanished race of people who came from the Europe, Africa or the Near East. Many early scholars believed the Mound Builders were one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. They believed the Mound Builders vanished and were replaced by the American Indian.

In 1881 the Congress of the United States gave $5000 to the Smithsonian Institution to conduct archeological excavations relating to the prehistoric Mound Builders and prehistoric mounds. Mr. Wills de Haas of Wheeling, West Virginia, was placed in charge of the project. Mr. de Haas who had studied Grave Creek Mound at Moundsville, West Virginia, resigned after a year. Cyrus Thomas replaced him and the project continued until 1890. In the Kanawha Valley W. P. Norris was in charge of the Mound Explorations for the Smithsonian Institution from 1882 to 1884.

The goal of the mound explorations was to settle the question of who were the Mound Builders. Were they an ancient vanished race as many scholars believed or were they the ancestors of the American Indians. By the completion of the project in 1890, over 2000 mounds and earthworks had been studied in the eastern United States. About 100 of these were in the Kanawha Valley. In 1894 Cyrus Thomas published his book Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology and proved that the Mound Builders were not a vanished race but the ancestors of the American Indian. This was the birth of modern American Archeology.

Once the question of the identity of the Mound Builders was settled, archeologists were able to begin tracing the development of North American Indian culture. Today we know Indians lived in the Kanawha Valley at least 12,500 years ago.

Mound Building

Mounds are like tombstones in our cemeteries today. The Adena people buried their dead leaders in log tombs. The tombs were covered with a mound of dirt. Burials were sometimes added later and another mound of dirt was placed over them. Some large mounds may have several layers of burials and dirt. The dirt for the burial mounds was dug from areas nearby and carried to the mound in baskets. Archeologists have found the impressions of these baskets during the excavation of some of the Adena mounds.

These burial mounds were monuments to the dead, and only important community or religious leaders were buried in the large mounds. Common people were buried in stone mounds that are often found on the hills and along the ridges overlooking the Kanawha Valley. The dead were sometimes cremated and their ashes were also buried in mounds.

Criel Mound in South Charleston is the second largest burial mound in West Virginia. In 1883 the Smithsonian Institution dug a deep hole into Criel Mound and found an Adena leader and ten of his servants. The leader was buried with a copper headdress, six shell beads and one flint knife. The other ten people were buried with him so they would be together in the after-life, the spiritual world after death.

How prehistoric people lived.

Homes

Prehistoric Indians in the Kanawha Valley did not live in tipis! In fact, prehistoric Indians east of the Mississippi River did not live in tipis.

Just as they do today, styles of houses changed through time. Nothing is known about Paleo-Indian and Archaic houses in the Kanawha Valley, but archeologists have found evidence of Woodland and Fort Ancient houses.

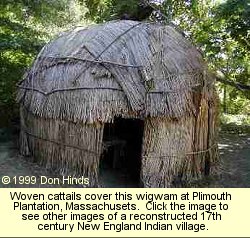

Woodland Indians lived in wigwams. These were circular houses made by sticking poles into the ground, bending and tying them at the top. This made a circular frame that the Indians covered with large slabs of tree bark or mats woven of cattails and bulrush. Wigwams were sometimes used as temporary houses. Saplings for the poles and tree bark for the covering were readily available throughout the Kanawha Valley. If woven mats were used they were easily transported and could be taken to a new location where new saplings could be cut for the poles.

Fort Ancient Indians lived in much larger square or rectangular houses. These were permanent houses but were also constructed with poles stuck into the ground. The sides were also covered with tree bark or woven mats. The roofs were covered with grass bundled for thatching. Some Fort Ancient people constructed their houses by weaving sticks between the poles and smearing the sticks with wet clay. When the clay dried it was hard as plaster and made a solid wall called "wattle and dab".

Indians also used temporary structures like rockshelters. Sometimes they stuck poles into the ground in front of the shelter and covered them with brush, hides or matting to form windbreaks so the shelters would be warmer.

The most important tools used by the Indians in building houses were their stone axes. The axes used by the Archaic Indians had a groove around them where the handle was attached. The Woodland and Fort Ancient Indians used ungrooved axes or celts for cutting trees and building houses.

Hunting

In the very early days, the Paleo-Indians hunted mammoth, mastodon, caribou, and other animals no longer living in West Virginia. After these animals disappeared, deer became the main animal hunted. Prehistoric Indians also ate many smaller animals such as wild turkey, fish and rabbits. Hunting tools changed over the years.

Paleo-Indians hunted mammoths and large game animals with large spears tipped with large fluted points made of flint.

The Archaic Indians used a spear thrower and smaller spears tipped with flint projectile points. These spears were made of two parts, the shaft or main spear and the foreshaft or front of the spear with the flint projectile point. This two-piece system made it easy to change broken points while hunting. The foreshaft with the flint point could also be taken off and used as a knife for cutting up plants or animals.

About 1200 years ago the Woodland Indians began using the bow and arrow. Their arrows were tipped with very small triangular flint points. The bow and arrow was faster and more accurate than the spear thrower.

Gathering

Prehistoric Indians ate more plants than meat. Plant foods were more plentiful and easier to get! Women and children gathered nuts, roots, berries, seeds and leaves of plants while the men hunted.

Prehistoric people used nuts and seeds like we use corn and wheat today. They made flour and meal for breads, soups, and stews. Prehistoric people ate a lot of seeds from plants that we call weeds, such as lambsquarter.

Women and children carried nuts, seeds, leaves and roots in baskets and bags. They dug roots with digging sticks.

Gardening and Farming

Besides gathering, the Woodland Indians began gardening or growing some of their own plants. Gardening was just another way of insuring enough to eat. Weed seeds and wild plants were just as nutritious or even more nutritious as many of the foods we eat today. Gardening insured that there would be plants available near to the home and people would not spend as much time in search of wild foods.

The Woodland Indians grew sunflowers, gourds, squash and several seeds such as lambsquarter, may grass, sumpweed, smartweed and little barley. Many of these seeds are considered weeds today and have not been grown for food in the Kanawha Valley for over a thousand years.

The Fort Ancient Indians can be considered true farmers. They cultivated large agricultural fields around their villages. They no longer grew such a variety of seeds but concentrated on growing corn, beans, sunflowers, gourds and many types of squash including the pumpkin. They also grew domestic turkeys and kept dogs as pets.

Cooking and preparing food.

Indians used several methods of cooking and preparing foods. Plant and animal foods were cut into pieces with flint knives. Nuts were opened with hammerstones and nutting stones.

The most common and earliest method of cooking was simply to roast meats, fish and some plant foods over an open campfire.

Before pottery was invented the Archaic Indians used a cooking technique called "stone boiling". Rocks were heated in a fire and then were placed in a deer hide or bark basket containing water and food. The heat from the red-hot rocks made the water boil quickly and cooked the food in about one hour.

About 3000 years ago the Archaic Indians began making bowls of sandstone and soapstone and began cooking food in these bowls directly over a fire. Shortly after this the Woodland Indians began making pottery cooking vessels and soups and stews became the most common meal of the Woodland and Fort Ancient Indians.

Clothing and Jewelry

Common Indian clothing was made of deer hide. The men wore loincloths and the women wore skirts and during cold weather both wore robes made of animal skins. Some clothing was made from woven cloth but this was reserved for community and religious leaders. Fragments of cloth worn by the Adena Indians have been found in the Criel Mound excavated by the Smithsonian Institution.

Sometimes the deer skin skirts and robes were decorated with seashells traded from the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. The community and religious leaders had their robes decorated with hundreds of seashells that were sewn on to form intricate designs. Seashells were also used for necklaces, bracelets and were worn around the ankles. When seashells were not available, beads were cut from deer and turkey bone. Animal teeth were also used for ornaments. Replicas of animal teeth were also made from shell and cannel coal.

People often wonder what the Indians in the Kanawha Valley looked like and how they dressed. Small clay figurines found at the Fort Ancient Village at Buffalo show Indian hair styles and tattoos or body paintings.

Community and Religion

Prehistoric people wore ornaments to indicate important positions of leadership in the community. Some important positions in a prehistoric community were community leader (like a mayor), Religious Leader (like a priest), medical leader (like a doctor) and club or organization leaders. Community leaders were often identified by a copper gorget or shell mask worn around the neck. The Adena leader buried in the Great Smith Mound had a copper reel shaped gorget on his chest. He also wore six heavy bracelets of native copper on each wrist. The copper was traded from the Great Lakes area.

Fort Ancient leaders wore gorgets or masks carved out of large seashells. Sometimes the masks had human faces with weeping eyes or stylized rattlesnakes carved on them.

The Adena Indians used pipes for ceremonies. They were carved of stone and they were exceptional works of art. Pipes and the smoking of tobacco became more common during the Late Prehistoric period. They were often made of clay and rather plain.

Tool Making

Prehistoric people made tools out of common material like stone, bone and wood. They made everything they needed without metal, plastic and electricity.

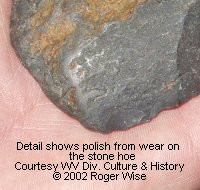

Arrowheads, knives, scrapers and drills were made from flint, a hard stone found along the banks of the Kanawha River. First a flake (small piece of flint) is struck from a large chunk with a hammerstone which is a simple cobble found on the riverbank. Next the flake is roughly shaped into a tool with a hammer made of deer antler. Finally very small flakes are pressed off the tool with the tip of a deer antler. This deer antler flaker is used to finish shaping and to sharpen the tool. If a flint tool becomes dull from use it can be resharpened using an antler flaker.

Prehistoric people used two types of drills. Drills were made of flint in the same manner as arrowheads were made. These flint drill bits were attached to sticks and twirled between the hands or powered by a bow. They made a cone shaped hole and were used on shell, wood, bone and sometimes stone.

Stick and sand drills were used on stone. A groove was made in the stone and a small amount of sand was placed in the groove. A hollow stick the size of the groove was twirled in the groove causing the sand to cut through the stone. This method made a tubular hole with straight sides and was used on pipes and spear thrower weights. To make a hole through a spear thrower weight would take about 12 hours.

Pottery was made with clay dug from the riverbank and mixed with crushed mussel shell. The bottom of a pot was formed from a lump of this clay mixture. It was beaten into shape using a wooden paddle on the outside and a river cobble on the inside. Clay was rolled into coils that were added to the rim of the base to make it larger. The paddle and river cobble were used to make the coils thinner and to finish shaping the pot.

Summary

The prehistoric Indians of the Kanawha Valley were an interesting people whose many remains can still be found today. We can continue learning more about these fascinating people only if we continue to preserve their archeological sites. Many of the mounds and earthworks originally recorded by the Smithsonian Institution in the late 1880's have been destroyed. Many other sites which still exist today have not been properly recorded.

If you have information on unrecorded archeological sites in the Kanawha Valley or anywhere in West Virginia contact the West Virginia Historic Preservation Officer, Department of Culture and History, Cultural Center, Charleston, West Virginia, 25305.

If you want further information or wish to purchase publications on West Virginia archeology, contact the West Virginia Archeological Society, P.O. Box 3854, Charleston, WV 25338. You can also find them on the internet at https://wvarch.org.

Bibliography

Braley, Dean

- 1993 The Shaman's Story, West Virginia Petroglyphs.

Dickens, Roy S., Jr. and James L. Mckinley

- 1979 Frontiers in the Soil: The Archaeology of Georgia. Frontiers Publishing Company, LaGrange, Georgia.

Jefferies, Richard W.

- 1987 The Archaeology of Carrier Mills. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale.

Lewis, Thomas M. N. and Madeline Kneberg

- 1958 Tribes That Slumber. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

McMichael, Edward V.

- 1968 Introduction to West Virginia Archeology. West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey, Morgantown.

Nabokov, Peter and Robert Easton

- 1989 Native American Architecture. Oxford University Press, New York.

Potter, Eloise F. and John B. Funderburg

- 1986 Native Americans: The People and How They Lived. North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Thomas, Cyrus

- 1894 Report on the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Wavra, Grace

- 1990 The First Families of West Virginia. University Editions , Inc., Huntington.

Weatherford, Jack M.

- 1988 Indian Givers. Crown Publishers, Inc., New York.

Wilbur, C. Keith

- 1978 The New England Indians. The Globe Pequot Press, Chester, Connecticut.

Video Resource:

Secrets of the Valley: Prehistory of the Kanawha

(on The Archaeology Channel)